Trickles of Optimism in Water Infrastructure

The water industry pulled through another year of mixed economic signals, deep federal budget cuts, and continued pressure from tightening regulatory requirements.

Meanwhile, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) released its 2013 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure, and the results were less than encouraging. The water and wastewater sectors showed minimal infrastructure improvement, inching along to a “D” from a “D-” grade four years ago, reaffirming the huge discrepancy between infrastructure improvement needs and funding.

More Annual Report & Forecast

As the gap between need and funding continues to grow, so does the number of reports outlining the financial reality: $300-plus billion needed to address the nation’s sewage collection and treatment infrastructure needs, and $384 billion in improvements needed for drinking water infrastructure in the next 20 years, according to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) surveys.

Despite the progress made in the construction and operation of water and wastewater facilities since the passage of the Clean Water Act and Safe Drinking Water Act, public investment in water and sewer infrastructure has been falling since the 1970s.

Current EPA reports estimate that there are more than 1 million miles of water main in the United States, and the condition of much of this pipe is unknown. Although approximately 4,000 to 5,000 miles of drinking water main are replaced annually, 700 miles of pipe burst each day, and leaky pipe wastes an estimated 7 billion gallons of water.

The numbers are staggering, and the need to invest in infrastructure is evident—as is the age-old question: “Who will pay?”

Preventing water loss

Leaky pipe, however, does a lot more than waste water, flood roads, and create sinkholes—it also further drains municipal budgets.

A system struggling with high water loss faces numerous problems. It requires suppliers to extract, treat and transport greater volumes of water; all of these processes lead to greater energy use. Eventually, leaks and main bursts find their way into waste and storm water collection systems, resulting in additional treatment expenses. These factors, coupled with high operational expenses, have made it almost impossible for water loss to be ignored.

Optimistic outlook for water

The Water & Wastes Digest 2013 report indicates that over the next 24 months, the largest percentage of respondents’ budgets will be invested in pipe and distribution, sewer and collection, and monitoring systems, jointly accounting for 31 percent of their budgets. It is likely that this will remain an ongoing trend as more utilities identify water loss prevention as an opportunity for reducing operating costs and increasing revenue.

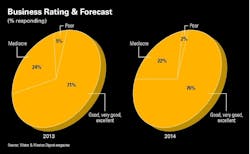

Despite aging systems and funding uncertainty, optimism seems to be trickling in for 2014.

More than three-quarters (76 percent) of respondents expect a good, very good or excellent business year in 2014, in comparison with 22 percent who predict 2014 will be mediocre and 2 percent that it will be poor.

Additionally, about 65 percent of respondents rate the overall health of their organizations as good or very good, in comparison with 26 percent who rate them as average and 9 percent who rate them as weak or very weak.

Average municipal water and wastewater budgets reached $2.8 million in 2013, up from $2.5 million in 2012. While 51 percent of survey respondents do not expect budget changes in 2014, 39 percent are projecting budget increases and only 10 percent are expecting decreases.

Although budgets jumped significantly from 2012 to 2013, about half (51 percent) of respondents said that their total municipal operating costs have gone up by 10 percent on average.

Private dollars

As the nation’s water infrastructure continues to surpass its expected lifespan and municipalities struggle to further stretch barebones budgets, managing capital and operating costs efficiently will take center stage.

Meanwhile, traditional approaches to infrastructure funding, such as obtaining bond market capital or relying on state revolving funds, will become less and less adequate. This does not mean that water and wastewater infrastructure projects will be neglected—water will continue to pour from the tap and toilets will continue to flush. It may, however, push municipalities to pursue alternative financing options, including turning to the private sector for help. Although negative perception of water system privatization remains strong, it will not be a question of “if” but “when” and “how” private dollars come to the rescue.