Utilization: The Cornerstone of Fleet Management

More on Utilization

- Increase utilization across equipment types.

- Utilization rates enable fleets to more accurately compare equipment costs.

- How wasted equipment hours define work status.

- What does 100% availability mean?

In this article, you will learn:

- The definition of utilization.

- How utilization is wasted.

- How to calculate utilization.

The fact that a machine is in your fleet does not mean that you can assume it is working to produce completed construction and contribute to the bottom line. Many things can go wrong, and many things make it difficult to achieve the utilization required to justify your investment.

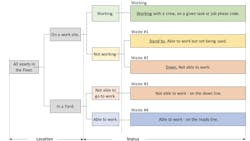

The diagram below shows that two factors contribute to the problem:

- The location of the machine. It can be on a work site where it stands a chance of working to support a crew, complete a given task, or contribute to a job phase code; or it can be in a yard where it is “off hire” and stands no chance at all of earning its keep.

- The status of the machine. It can be working, able to work but not required to do anything, or it can be broken down and unable to work for a mechanical or safety reason.

Time spent on site and working is the only time when a machine can produce a return on investment. All the other times are waste. Utilization measures success in reducing these wasted time periods and is the cornerstone of everything done to improve fleet performance.

Let’s review the five endpoints in the diagram and see what we can learn about utilization.

Working. The time a machine spends working to produce completed construction by supporting a crew, working on a given task, or contributing to a job phase code. It is the numerator in the utilization calculation and the single most important metric of all fleet management metrics.

Working time absolutely must be defined and measured, and there must be agreement on both the definition of “hours worked” and on the value achieved by each machine each day. Nothing is achieved if there is no single source of truth regarding hours worked.

Waste #1. The time a machine spends on site, able to work but not being used due to delays and disruptions in the flow and sequence of the work. This is a significant waste that can only be managed by the teams responsible for planning the work and driving production in the field. Mechanisms must be in place to ensure that this waste is measured and that the leadership responsible for planning and sequencing operations is held accountable.

Waste #2. The time a machine spends on site but not able to work due to some mechanical or safety reason. This is the responsibility of the teams involved in Field Maintenance Operations. It must be measured and managed. Field maintenance operations must be accountable—delays and disruptions due to lack of reliability and downtime must be reduced to a minimum.

Waste #3. The time a machine spends in a yard or storage area not able to go to work for a mechanical or safety reason. This is a clear responsibility of the teams involved in Shop and Yard Operations. Resources must be available, and strategies must be in place to reduce this to an absolute minimum. Nothing is achieved by having money invested in broken down assets standing idly in the yard.

Waste #4. The time a machine spends in a yard or storage area able to go to work but without the opportunity to do so. This is a fleet balance, strategic planning, corporate issue. The construction industry constantly changes, markets and opportunities change, and fleets must change. Nothing is achieved by having money invested in assets standing idly in the yard.

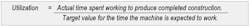

Most companies use the following calculation to define utilization.

Defining and measuring the numerator—the actual time spent working to produce completed construction—is complex. The following are common alternatives:

- Working time recorded by an manufacturer-installed or J1939-based telematics system that may or may not exclude the short periods of “at idle” or stand-by time normal to all construction operations.

- Working time recorded by a GPS/geofence system with accelerometer or wired sensor and defined as the time between “key on” to “key off.”

- Working time recorded by a supervisor on a Daily Job Cost Report (DJCR) as the time spent supporting a crew, working on a given task, or contributing to any number of job phase codes.

Defining and measuring the denominator—the target value for the time the machine is expected to work—is also complex. The following are common alternatives:

- Time the machine is deployed to site and expected to work minus any down time.

-

Time used in the owning cost portion of the rate calculation when setting the hourly rate required to recover the estimated fixed monthly owning costs.

- A straight 8 hours per day or 40 hours per week on site.

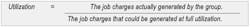

The importance of utilization to the company has led to the use of a method able to summarize the utilization of a large group of machines based on a comparison between the job charges actually generated by the group and the job charges that could be generated if all the units in the group were fully utilized.

It appears complex, but it is not. The job charges generated by units in the group are calculated regularly and can easily be summarized at a group level.

The job charges that could be generated at 100% utilization is a simple calculation based on all the internal rates for the various machines in the group.

The importance of utilization in the fleet and asset management process certainly merits the use of this metric.

Utilization is the single most important metric when it comes to managing a fleet. You absolutely must agree on how you define it and how you collect the data required to calculate it.

Keep it simple, make sure that you collect and verify the required data consistently, and make sure that your results are communicated and understood. Use utilization to measure success in eliminating waste and remember that a machine is only an asset when it is contributing to the bottom line. At all other times, it is a liability.

About the Author

Mike Vorster

Mike Vorster is the David H. Burrows Professor Emeritus of Construction Engineering at Virginia Tech and is the author of “Construction Equipment Economics,” a handbook on the management of construction equipment fleets. Mike serves as a consultant in the area of fleet management and organizational development, and his column has been recognized for editorial excellence by the American Society of Business Publication Editors.

Read Mike’s asset management articles.