Smarter Excavators Toughen Up

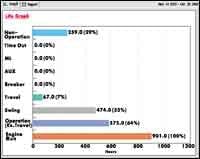

- Average Excavator Costs

- Excavator Specs: 30- to 40-Ton Base Models

- Hyundai

- Volvo

- Case

- Hitachi

- JCB

- John Deere

- Caterpillar

- Daewoo

- Komatsu

- Link-Belt

Computers installed in today's 30- to 40-ton hydraulic excavators have taken a crucial step up to a level of sophistication that they can actually make production decisions, but innovations in this product category are not all electronic. Equipment manufacturers have also made impressive improvements the old-fashioned way—investing research and development dollars into more powerful engines and hydraulics, more effective cooling systems, longer-lasting linkages and longer service intervals.

The Environmental Protection Agency's 2003 Tier-II emissions deadline brought engine updates across the 30- to 40-ton excavator class. With their electronic fuel-injection controls, virtually all of the engines are more powerful than engines used in preceding models (up to 19 percent more horsepower). And with the ability to fine-tune fuel injection as the work changes, most of the new engines use in the neighborhood of 10 percent less fuel.

Combine electronic engine controls with second- and third-generation computers on hydraulic systems, and the latest generation of excavators are so smart that they're behaving like production advisors on the job. For example, machine controllers offer operators the choice of multiple work modes, each designed to assign hydraulic priority to the circuits most critical to production in common excavator jobs—stick and boom get flow priority, for example, in the digging mode; and the attachment circuit gets priority in attachment mode. The problem with previous generations of excavators is that operators had to be trained to use the right mode at the right time. That seldom happened, and productivity and efficiency suffered when work was done in the wrong modes.

To simplify the choices, many of today's machines offer an Automatic mode. The machine's computer senses system pressure and the operator's lever inputs, then adjusts hydraulic priorities automatically to accomplish more efficiently what the operator wants to do.

Caterpillar has eliminated work-mode selections from its 325C L and 330C L. Most other manufacturers have limited the choices to Automatic mode and one or two other choices (often just Digging and Attachment modes). But a few manufacturers, such as Komatsu and Hyundai, continue to offer a range of manually selected work modes. Komatsu's Galeo system has Active and Economy work modes, a Lifting mode, and a Breaker mode. Plus two boom settings—Smooth and Power—allow operators to customize each work mode. Hyundai offers a similar control scheme, with Heavy Duty and General settings, plus a Breaker mode. And the operator can choose High Power or Standard Power in each mode.

Sensors in the hydraulic systems integrated with controllers on both the hydraulic pumps and engines have made the power-boost feature common. If the machine's working circuits reach standard relief pressure for more than a second or two in tough digging, the systems automatically boost main pressure about 10 percent for a short period (usually around 10 seconds). Machines can handle the heavier load for short spurts, and the extra power can help push through a tough job. Several manufacturers put a button on the joystick that operators can push to boost power on demand.

Some excavators are also sporting the first real data loggers that manufacturers have installed on machines. Deere and Hitachi's Machine Information Center, for example, records all operating parameters—things such as engine speed, coolant temperature, hydraulic pressure and temperature, travel time, swing time, idle time, fault codes, alarms and more. That data can be downloaded easily with a hand-held computer. Once it is uploaded to a personal computer, it can be graphed for easy analysis.

"You can look at what your excavator's been doing for a month," says John Deere's Mark Wall, excavator product manager. "If there's a lot of idle time, you may decide you need another truck on the job. You can pull pump histograms to see how hard pumps have worked. If they've averaged 2,500 psi instead of 4,000 psi for the last 9,000 hours, you may decide not to overhaul them before sending that machine out to a big job."

Technology is improving durability and ease of service, too. For example, today's engines in the 30- to 40-ton excavator class have more heat to dissipate because of intercoolers between turbocharger and cylinder head, so many machines are now cooled by a fan with hydrostatic drive. Responding to information from a thermostat, the engine controller tells the hydrostatic fan drive when to come on and how fast to run. The fan uses only enough power to hold the engine in a safe operating-temperature range. Deere and some others have added an airfoil fan to variable fan drive to save significant horsepower.

It's not a coincidence that there's a service-interval race going on in hydraulic excavators at the same time so much electronic technology is being applied to the machines. Most of the diesel engines in today's excavators are designed for 500-hour oil-change intervals. The engines are working harder than ever, but computer controls have softened the sharp peaks in horsepower demand and they monitor and respond to coolant and oil temperatures and pressures better. New filter technologies are buying time for oil, too.

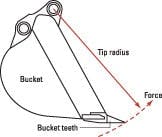

In the interest of aligning basic service at the same interval as the engine-oil change, manufacturers are applying special metallurgy and seals to bushings and pins in boom, stick and bucket joints to stretch greasing intervals. John Deere and Komatsu excavators are at 500 hours, and all the front-linkage pins except for the bucket joints on Cat and Case machines now require grease only at 1,000-hour intervals.

High-end hydraulic filtration, and more-effective cooling have extended hydraulic-oil service intervals as long as 4,000 hours. For example, Link-Belt's LX Series machines come standard with a factory-installed bypass filtration system called Nephron.

Other iron innovations include Komatsu's importing the minimum-tail-swing concept to the 30- to 40-ton size range last year. The PC308USLC-3 maintains its balance with an 18,000-pound counterweight and slightly extended track gauge. With a loaded bucket, it can turn 360 degrees within 17½ feet.

When you ask manufacturers' excavator product managers which single technology had the greatest impact on their product category over the past 24 months, virtually all of them talk about electronic controls that now do more than just sense conditions. They provide feedback—either at the monitor, or in the form of adjustments to hydraulic and engine performance. It's a sophistication bordering on artificial intelligence that makes the machines more effective and efficient. Electronic systems provide information that improves diagnostic ability and helps owners make the best choices about how to use the machine effectively.

Electronics warrant a lot of attention because they are beginning to automate mainstream production machines. The good news for buyers who have to make a living with the machines long after the "gee-whiz" has worn off is that today's innovations are not all gee-whiz. The same high-tech that makes this excavator class smarter and more productive is also making the machines more durable and easier to service.

| Web Resources | ||

| Case www.casece.com |

||

| Caterpillar www.cat.com |

Daewoo www.dhiac.com |

|

| Hitachi www.hitachiconstruction.com |

Hyundai www.hceusa.com |

|

| JCB www.jcbna.com |

John Deere www.deere.com |

|

| Komatsu www.komatsuamerica.com |

Link-Belt www.lbxco.com |

|

| Liebherr www.liebherr.com |

Volvo www.volvo.com/constructionequipment |

|