Key Highlights

In this article, you will learn:

- How to align capex planning with corporate objectives.

- The three parts of a capex budget.

- How to make effective decisions regarding capital investment.

- Key financial strategies for budgeting.

Editors note: Originally published in July 2014, this article has been updated.

Equipment is a capital-intensive business, yet capital is a scarce and expensive resource. That is why so much of what we do is focused on capital expenditure (capex) and the capital-expenditure budget.

Developing the budget and making the business case for the substantial capital investments needed to stay in business are not easy. Yet the investments you make—or do not make—today will play a major role in the future of your company.

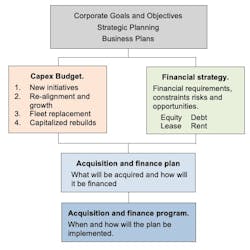

Let's understand some of the challenges and the processes we can use to unscramble the problem and make better decisions. The nearby diagram shows the essential steps.

Align capex with corporate objectives

Capital investments should not be made on a whim. Corporate goals and objectives must be clear, and an effective decision-making process must be in place to guide investment decisions. Competent capital budgeting starts with a clear understanding of the business, where it is going, what opportunities it will pursue and how it will flourish in the future.

The capital expenditure budget (capex budget) must be a well-considered and thought through “wish list” of the capital investments needed to ensure that equipment assets are available and able to support planned operations reliably, efficiently and economically. The budget must be comprehensive and each item must be justified and prioritized. The capex budget is nothing more than a dream unless it is accompanied by a coherent and workable financial strategy that recognizes the realities of existing constraints and breaks away from the naive assumption that everything will be bought for cash.

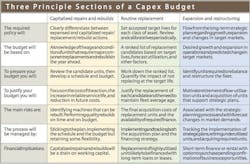

Equipment capital budgets can conveniently be broken down into three sections.

1) Capitalized repairs and rebuilds

The first portion of the capital budget focuses on the funds required for capitalized repairs and rebuilds on identified units. A lot depends on a company’s policy regarding capitalized or expensed repairs. Undercarriages and major component replacement are good examples. Will they be capitalized or expensed?

The process, therefore, starts with a clearly defined policy and a good definition of what will and what will not be capitalized. Companies with liberal repair capitalization policies need to take care and ensure that repair costs do not get lost by rolling them into the depreciation portion of the owning cost calculation. Undercarriage costs are an operating cost regardless of whether or not they are capitalized. Expensed and capitalized repair costs must be added together when determining hourly operating costs.

The repair capex budget must be based on the capitalization policy and a good knowledge of the age and condition of existing units that will require major component replacements or rebuilds in the year ahead. The budget will be prepared by reviewing the candidate units, developing a major repair and rebuild schedule, developing an execution strategy, and setting a budget for each action.

Justification will be based on three things: the cost of the action, the increase in reliable serviceable life arising from the action, and the reduction in future operating cost attributable to the action. It is not a complicated calculation, but it is a high-risk calculation: Not all machines have the inherent quality and structural integrity needed to obtain the increase in reliable performance life required to justify extensive rebuilds.

The resulting budget will be managed according to the planned schedule and estimated cost for each action. It appears simple, but unplanned component failures invariably cause change and disruption. Adding a contingency for unknowns is a good idea but difficult to justify in tight times. Capitalized repairs and rebuilds are unlikely candidates for financing, and costs will be a drain on working capital.

2) Routine replacement

Under normal circumstances, this is the largest portion of the capex budget and is where managers consider questions of economic life, deferred replacement, and productive hours in stock (see June 2012, March 2013, and March 2014). It appears complex, but you cannot deny the bottom line: Machines get used up in the production of work, and they must be replaced at some point in time.

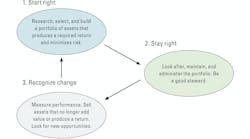

Again, it starts with a competent policy together with the courage and financial resources to do the right thing at the right time. You absolutely have to have a policy to replace your core fleet on a regular basis. The concept of economic life—the period that ends when the life-to-date owning and operating costs reach a minimum—is well articulated and well understood.

The formal calculation is a little complex in that it relies on good data and computations that go beyond the simple. This must not be seen as a reason for not implementing a systematic replacement policy. Best policies are based on good judgment and periodic calculations to calibrate benchmarks and ensure that things stay on track.

Define a replacement policy, implement it, stick to it, and calibrate it from time to time. Estimate future utilization and base the budget on a ranked list of replacement candidates with the numbers to justify each decision. Your budget will be prepared by working down the ranked list and quantifying the impact on both cost and productivity of not replacing candidates at the required time.

The justification for replacing each candidate should speak for itself as should the need to maintain fleet average age at or around the economic life for each class of equipment. There are small but not insignificant risks associated with the cost and availability of replacement units and the required finance. High-utilization, low-risk core fleet is likely to be financed with equity, long-term loans, or leases. The entire acquisition and financing process needs to be carefully managed according to a preset plan.

3) Expansion and restructuring

This is the most speculative and difficult section of a capital expenditure budget. The need flows from the long-term planning and market-review process conducted at an organizational level and from strategic plans regarding expansion or changes in the market. It is absolutely essential to realize that things do not stay the same and that there are constant shifts in the market place.

Equipment selection and fleet balance decisions are long-term decisions that must be taken within a competent strategic framework. You may be able to buy and sell on a whim, but costs are invariably higher and results are invariably less than satisfactory.

The capex budget for equipment in this section must be based on desired growth and expansion, and on predicted changes in the market place. Required units will be identified for acquisition, and equally important, existing units with a bleak utilization future will be identified for disposal.

Justification is based on the strategic plan and from a commitment to keep the company in the best possible position for what may happen in the future. Risks are many: All are associated with our inability to see clearly past immediate opportunities. Uncertainty about the future will most likely dictate the use of shorter-term finance or rental agreements with purchase options pending confirmation of the business opportunity.

The table below summarizes the essential features of the three principal sections of a capital expenditure budget. The differences, complexities and risks are clearly apparent. Breaking the process down as shown in the three columns makes it possible for equipment managers to focus on the task at hand. It is an important part of our business, and using the three-part approach will help us do it well.

The realities of financial strategy and the steps needed to maintain desirable balance sheet ratios will invariably require a number of compromises and complex decisions regarding capex priorities and financial realities. What you buy is important; how you finance it is critical.

It is therefore important to develop a realistic, robust, and financially astute acquisition and finance plan. Every form of finance—equity, debt, lease and rent—has its risks and rewards that must be considered. The computations are complex and, regardless of which alternative appears best, the and plan will have to consider factors such as:

- The availability of cash and need to maintain working capital and liquidity.

- The debt equity ratio and the need to reduce long-term financial commitments and maintain defined balance sheet ratios.

- The need to to maintain flexibility and minimize the high risk fixed costs associated with loans and leases.

- The ability to obtain favorable terms and share risks in areas such as residual value by continuing to work with dealers and manufacturers.

- The need to hedge your bets, “try before you buy,” and build equity in your fleet by entering flexible rental purchase agreements.

The acquisition and finance plan integrates the capex budget with the company’s financial strengths and tax position. It maximizes the availability of funds and reduces risk by assembling an appropriate portfolio of financial resources. The plan requires careful implementation over time. When and how it is to be implemented is detailed in the acquisition and finance program.

The questions, of course remains: How big should the capex budget be and how much is enough? There is no answer.

Capital investment in a business is entirely dependent on plans and aspirations. If a steady state or organic growth situation is desired, then clearly the company must “buy what it burns” and invest at least enough to maintain fleet average age and realign its fleet to meet changes in the market place.

The “buy what you burn” calculation is relatively simple and straight forward. Each year a certain number of machine hours in a given category is “burned up” in the production of completed construction, and therefore, each year (or each couple of years) new units must be purchased to replace the machine hours used up.

Some companies index their capital expenditure to contract revenue earned in the past year. Others, perhaps more appropriately, index capital expenditure to backlog or new contracts awarded. This makes sense because you are in fact, making capital investments for the future because you are building for the future.

It is not difficult to do the calculations, but it is difficult to develop a comprehensive acquisition and finance plan that supports the capex budget and fits within the reality of a well thought out financial strategy.

About the Author

Mike Vorster

Mike Vorster is the David H. Burrows Professor Emeritus of Construction Engineering at Virginia Tech and is the author of “Construction Equipment Economics,” a handbook on the management of construction equipment fleets. Mike serves as a consultant in the area of fleet management and organizational development, and his column has been recognized for editorial excellence by the American Society of Business Publication Editors.

Read Mike’s asset management articles.