Actions Speak Louder than Budgets

Developing topics for these articles has benefited greatly from the opportunities I have to talk and interact with the best in the business. Never more so than in this article where I draw heavily from a conversation that explored a very simple concept: If you want to win, keep your eye on the ball not the scoreboard.

Many managers spend too much time accounting for cost rather than taking action to minimize or eliminate the causes of cost. We routinely check and approve invoices and argue over back charges for a cracked windscreen. We seldom have time to investigate why or how the damage occurred in the first place or take action to ensure that it will not happen again. We emphasize cost control but forget that if you perfect and win every play, the scoreboard will follow.

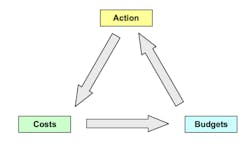

Costs do not just happen - they arise because of the action we take to address issues, solve problems and optimize the future. The costs we experience work their way into budgets that measure performance and encourage appropriate action. It feeds on itself; – the right action, lowers costs, improves budgets and prompts more good work. It can also go the other way; do the wrong thing, costs go up, budgets get worse everything spirals downwards.

Let's review four things we can do to win the game and produce a scoreboard that reflects our success.

1. Run an effective, respected organization.

A number of prior articles deal with organization structure and the pros and cons of centralizing or decentralizing fleet management. It is a complex issue but the bottom line is simple; equipment and field operations share and contribute equally to the principal company objective – to produce completed construction on time and on budget. Placing the shared common interest of the company first makes it possible for equipment and field operations to value the contribution that each makes and emphasizes the fact that the two groups are mutually interdependent.

Personalities, experience, ambition and other factors often cause organizations to loose their focus and start playing intra organizational games of one-upmanship. No amount of finger pointing, cost reallocation or back charging can eliminate the costs experienced when an engine fails or when a superintendent abuses a machine simply because “the equipment department charges us too much anyway.”

It is hard to imagine that a company with a substantial investment in its fleet can be successful without an effective respected organization responsible for the lifecycle management of its equipment assets. This group, regardless of organization structure, can significantly reduce costs by emphasizing the balance between long term lifecycle driven decisions required to manage a fleet and the short term production driven decisions required to complete construction on time. Equipment managers often struggle with this and feel that their role is under valued. When this happens, they must return to basics and stress their role in reducing costs to the company as a whole. Emphasizing the value of the expertise you bring to the table is a better strategy than defending what some see as the added cost of your organization.

2. Understand the basic functions and do them well

Every company approaches the complex and difficult task of equipment management in its own way. There are, however, six basic functions that must be performed regardless of how the company is set up. (see Six functions of Machine Management, July 2006, page 68, 69 and Focus on Functions to Improve Performance, August 2006, page 95,96.) Focusing on the functions and doing them well will reduce costs and improve alignment between competency, responsibility and authority across the company.

The first two functions, acquisition and disposal and compliance and risk management combine to define the owning cost of the fleet and are minimized by bringing together operational planning, finance and administration to set capital budgets, obtain the necessary finance and manage risk at minimum cost.

The third function, transport and logistics, requires close interaction with job sites on a day to day basis to ensure that “the right iron is in the right place at the right time.” Costs are minimized by competent production planning and communication regardless of who carries responsibility or who pays for moving which machine.

The next two functions, field maintenance operations and shop and yard operations make up the operating costs. Here we see a need for close interaction between operations and equipment if costs are to be lowered. It truly does not matter who pays for a tire damaged by rocks on the haul road or whose budget carries the cost of a transmission damaged by incorrect operation. The costs have been incurred and the right thing to do is to take action to ensure it does not happen again.

The final function, fleet and asset management, brings together the expertise needed to ensure that the investment in the fleet produces the best returns. Good decisions must consider all stakeholders and the only way to improve return on the capital invested in the fleet is to focus on the fleet as a company asset regardless of who carries what cost and who has what budget responsibility.

3. Focus on prevention, drive for zero failures

There are three ways of writing work orders. The first way is to have the machine write them for you after it has broken down and disrupted carefully laid production plans. These work orders start with a paragraph that reads something like, “Sorry to have to call you out to this difficult place at this difficult time but my hydraulic pump has finally quit and I can not work any more. Please come quickly as there are a lot of annoyed production folk shouting and screaming at me and there are a lot of trucks standing waiting for me to work again. Sorry for the problem – it is a pity you never sent in the oil sample you took a couple of weeks back. If you had, you would have noticed some large particles that have been causing me a problem for a while.” These work orders are the worst kind. They are expensive and lie at the root of the belief that equipment managers care little about production.

The second way of writing work orders is to have them written whenever a clock ticks past a certain point. These will start with the following; “It is time to go and change the oil in the excavator. I know it will cost a lot but statistics show you should do it now. I do not know if it is necessary but it is the prudent thing to do. Who knows, you may be preventing a problem.” These are good, warm feeling type of work orders. They give the impression that you are on top of your game. They do, however lie at the root of the belief that equipment managers spend too much money.

The third way of writing work orders is to reach out to your fleet, listen and know what is going on. You write these work orders based on condition data you have collected . You send a copy to production and start with a paragraph that reads: “We have noticed some large particles in the hydraulic oil of the excavator. We will take it off shift at 7am next Wednesday. Please plan production on this basis. You can expect downtime to be short and costs to be minimized as we have the required people and parts on hand. Thanks for your cooperation – a pleasure to do business.” This is clearly the way to go. There will not be a disruptive failure, you will be doing the right thing at the right time and you will clearly be on top of your game.

Collecting data on the condition of your fleet and using this in a condition based maintenance program improves reliability, lowers cost. It shows you are on top of your game and clearly demonstrates the value of your organization.

4. Manage fleet average age

Many prior articles (see Buy What You Burn, October 2004 pages 63 – 64, The Intangibles of Fleet Average Age, November 2005, pages 86 – 87, Keep Capacity in Stock, November 2006 pages 66 – 67) emphasize the importance of making regular investments in the fleet in order to reduce the problems that occur when an unusually young fleet easily beats budget relative to established lifecycle norms or an unusually old fleet has no option but to exceed annual costs and budgets based on shorter more conservative life estimates.

There will be times when high investments bring average age down and there will be times when capital expenditure is reduced for good reason and we must all do what we can to get the most life out of the iron we own. This is part of the normal business cycle but it must be understood and managed. There is simply no such thing as a free lunch and reducing capital expenditure carries with it an obligation to the increased operating cost of the older fleet. Again, this is not an “equipment” problem that will go away by re-allocating costs, shuffling budgets or pointing fingers. Above all, nothing is achieved by looking at the scoreboard while the ball slips through your hands for yet another dropped pass.