Volunteer Now Before You're Forced to Clean Fleet Exhaust

If the state told you that you couldn't go to work before noon and barred any equipment that was built before 2003 from their projects, would you consider that a fair price to pay for clean air? Suppose they insisted that you use ultra-low-sulfur diesel fuel, which is only available in limited areas and costs up to 40 cents per gallon more than today's dyed on-highway fuel?

Sounds like a straightjacket, doesn't it? It's one that Texas tried to slip over the shoulders of contractors in the Dallas Metroplex and the Houston/Galveston area five years ago.

They did it in the name of clean air — a good cause. But contractors obviously did not participate in making those rules. When the ruling was announced, the local construction industry, galvanized by the Associated General Contractors (AGC) stepped in to interject some reason. Luckily, they prevailed — for the time being.

States are at the mercy of the Clean-Air Act and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The Clean Air Act requires EPA to set air quality standards for pollutants considered harmful to public health and the environment, and EPA established standards for six criteria pollutants. Older diesel engines contribute substantially to two of them — nitrogen oxides, one of the main ingredients in ground-level ozone and smog; and particulate matter, a potential cancer agent.

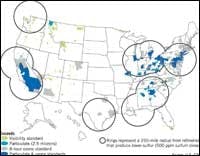

EPA monitors air quality around the country and when an area does not meet the standards, it may be designated as a nonattainment area.

Nonattainment areas must develop plans to clean up their air by specific deadlines, and EPA must approve these State Implementation Plans (SIPs).

EPA has the power to withhold some federal funding from states that fail to act to clear the air in their nonattainment areas. Texas is dealing with an air-quality problem in its major metro areas, just as Atlanta, Chicago, Boston, southern California and most of the country's largest urban areas.

The Texas SIP included two rules that focused directly on the construction industry's contribution to clean air. The construction ban prohibited use of any diesel equipment before noon basically from April to October. A second rule accelerated the pace of replacement of older diesel engines.

"Construction companies could not have absorbed the financial impacts of these tactics and remained viable," says Bob Lanham, vice president with Houston-area contractor, Williams Brothers Construction.

The Texas construction coalition lobbied intensely and prevailed on the state legislature to replace the rules with the Texas Emissions Reduction Plan (TERP). The voluntary grant and rebate program is funded from a number of sources, "not the least of which is a one-percent fee on the sale, resale and lease of diesel equipment," says Lanham.

TERP includes rebates for on-road vehicles, both light and heavy duty, and several grant programs. One subsidizes replacing off-road equipment with new, cleaner-running machines. Another grant funds the cost difference between rebuilding engines and repowering the machines with new diesels. There are grants for buying retrofit exhaust filters and using alternate fuels.

The program is well received and generously funded, but Lanham says it must ultimately succeed. It must be so widely used that its effects in cleaning up the air in and around Dallas and Houston are measurable.

"Its failure could bring reconsideration of the rules it replaced," says Lanham. "Just as we had to change our culture and manner of thinking with regards to OSHA, the same mindset shift must occur again with the Clean Air Act."

A serious challenge that Texas contractors face is a unique air-quality problem focused on NOx. Texas' two nonattainment areas are among the very few whose only criteria pollutant is NOx. There are few retrofit options to combat NOx in construction equipment.

"In diesel technology, catalysts are still an emerging technology in nonroad engines," says Lanham. "They haven't been able to reach the same performance as in on-highway applications because of the transient load curve of most off-road equipment."

As a result, Williams Brothers and most other Texas contractors have spent their grants repowering or replacing equipment. Emissions are cleaned up, but there isn't enough money to repower the entire Texas fleet.

"We're trying to foster an atmosphere where emerging technologies for NOx reduction in off-road equipment can get to market faster," says Lanham.

Southern California struggles under similar NOx pressure as Texas, plus the weight of many other criteria pollutants. The state's Carl Moyer Program has provided $98 million thus far in incentives to reduce NOx and PM emissions from heavy-duty diesel engines. Funds are distributed through local air districts, which select projects. Grants cover a portion of the cost of putting cleaner engines in all applications (see www.arb.ca.gov/diesel/mobile.htm).

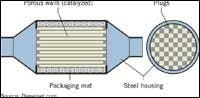

Most other nonattainment areas seem to focus on encouraging contractors to adopt simpler solutions for nonroad equipment — particulate traps and catalysts. The specifics remain at the discretion of each state's SIP.

"Lower emissions are required on the Dan Ryan project and I-294 tollway [in the Chicago area]," says Mark Lynes, equipment manager with Walsh Construction of Illinois. "All the big projects that come out in Cook County have this clause in them."

Lynes says contract specifications require any machine in the 50- to 300-horsepower range that will be on site for more than 30 days must either be retrofit with an exhaust catalyst or use diesel fuel with a sulfur content of 15 parts per million.

"There's a refinery in northwest Indiana that makes low-sulfur fuel, so we can get it here," says Lynes. "We pay about 45 cents in addition, with a delivery surcharge of about 15 cents per gallon. The refinery has to dedicate a truck to avoid contaminating it with higher-sulfur fuel."

Walsh has 40 to 50 machines running on ultra-low-sulfur diesel (ULSD) right now, and Lynes estimates the company is buying 15,000 gallons per month. There have been no problems thus far, but Walsh has only been using ULSD for about four months.

The company has nearly two years of experience with retrofitting exhaust traps. A demonstration program paid the cost of retrofitting seven machines with exhaust catalysts at the beginning of last-year's season. The number of retrofits in the Walsh fleet is up to 20 now.

"If it's a high-utilization machine that's going to burn lots of fuel, it's probably best to retrofit," says Lynes, comparing the retrofit alternative to burning ULSD. Deciding is a fairly simple matter of estimating how much fuel a machine will burn on a regulated project, multiplying that by the additional cost of ULSD, and comparing it to the retrofit cost.

"We just prepare the comparison for the project managers," says Lynes. "They make the decision, since they are ultimately going to have to pay for it."

Contractors choose their retrofit solutions from catalytic oxidizers on EPA's verified-technology list.

"Depending on the size of engine, some of these things can be huge — big cabinets the size of a beer keg mounted outside the engine canopy," says Lynes. "But they're not all that hard to handle.

"You have to meet certain backpressure requirements from the engine OEMs, but we have had almost no trouble with the machines."

Lynes recommends going to the OEM's engineers on every retrofit.

"Make sure they know what you're doing and you know what they recommend," he says. "And make sure we don't void any warranties."

The company has never been required to repower machines.

"We have swapped out some machines in Atlanta, though," says Lynes. "Their specs require equipment with a minimum of Tier 2 engines, so we just switch things out in the fleet so they get newer machines."

A crucial difference between the situation in Chicago and Atlanta and what's happening in Texas and California is that contractors in Chicago and Atlanta have no choice but to reduce emissions. The Texas and California programs are voluntary.

"The construction industry supports TERP in Texas," says Ken Simonson, chief economist with AGC. "It's a good model for other states to follow, rather than using mandates, regulation, and bidding-preference approaches.

"Bidding preference is an approach that cuts out otherwise qualified contractors from bidding on projects, and it can cost states a lot more on contracts with a limited pool of qualified bidders."

Of course the industry supports voluntary clean-air programs, but lip service cannot replace real action to improve emissions quality.

"There is no huge voluntary movement to put this stuff on," says Simonson. "In cases where states are providing incentives or where localities have restricted bidding, contractors have not had a problem with compliance. But retrofits require making an investment in equipment that doesn't necessarily improve productivity. Contractors are looking for incentives from state and federal clean-air funds."

EPA recently launched its National Clean Diesel Campaign to facilitate regional collaborations between businesses, government, and communities to provide incentives. Members of these initiatives have agreed to collectively leverage additional funds and take a local approach to diesel mitigation.

Uncle Sam is offering more than moral support for these collaborations. The federal government has made a number of recent moves to fund retrofit programs.

EPA created $1.4 million in grants intended to take advantage of more than $5.8 million in matching funds available through the West Coast Diesel Emissions Reductions Collaborative. The first of these grants freed up nearly $1 million of joint funding for a retrofit demonstration project in Sacramento. It will reduce diesel pollutants from heavy-duty equipment such as loaders, backhoes and excavators. Old mufflers will be replaced with lean NOx and particulate filter technology by Cleaire.

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 created the $1-billion Diesel Emissions Reduction Act, providing up to $200 million per year to reduce emissions from older trucks, buses, and off-road equipment. The Energy Policy Act also created a $100-million diesel-truck retrofit program that will fund up to half of the cost of modernizing large truck fleets.

"AGC lobbied successfully for, in the highway bill, a provision to allow CMAQ (congestion mitigation and air quality) funds to provide incentives for diesel retrofits for off-road vehicles," says Simonson, speaking of another new source of incentive cash. "Those funds were previously only available for on-highway vehicles."

Construction-equipment owners must make it a priority to participate in these programs if they hope to avoid business-stifling rules like those overthrown in Texas early in the decade. If nonattainment areas don't meet clean-air standards, voluntary programs will give way to regulation.

"States are inevitably moving toward tighter restrictions on diesel equipment," says Simonson, "and contractors will need to be part of the solution."

They will need experience with technology alternatives to formulate opinions about which are most effective. And those efforts will demonstrate a commitment to clean air that will give them real influence in the regulatory process.