A Lanyard, a Harness and an Anchor: 3 Items That Could Save Your Life

Remember those pictures of workers constructing the Empire State Building back in the early 1930s? On beams suspended a thousand feet up, they walked, they worked, and they even ate lunch, nary a look of worry on their faces. That's especially surprising considering nothing but good balance prevented them from falling to their death. Fall-protection equipment was almost unheard of in those days.

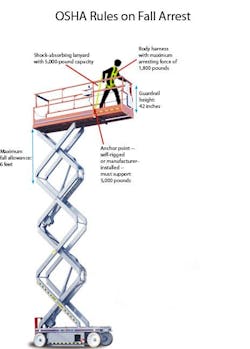

Today, however, fall-protection gear is mandatory, with safety regulations developed by the Occupation Safety and Health Administration as well as the American National Standards Institute. Still, hundreds of workers are injured or killed in fall-related accidents each year. According to OSHA, there were 809 fatal falls in 2006; most of them involved falls from roofs and ladders.

The complete list of OSHA rules can be found at www.osha.gov/SLTC/fallprotection/standards.html.

Although OSHA and ANSI have developed fall-protection rules for construction, workers still get hurt or die from falls for two reasons: Fall-protection gear is either used incorrectly or neglected completely.

Understanding fall protection

"One of the difficulties is getting people to understand how the equipment should be used, what the correct application is, and what an incorrect application is," says Geoff Locander, general manager of Sellstrom Manufacturing's RTC Fall Protection, a manufacturer of fall-protection equipment.

One of the first things that workers must understand is most fall-protection equipment does not prevent one from falling. Rather the equipment is designed to avoid fatalities and minimize injury in the event of a fall.

"We don't really protect against falls," Locander says. "The term 'fall protection' is kind of a misnomer. Our equipment and anyone else's is designed to arrest falls within the guidelines of OSHA and ANSI standards."

When workers believe that fall-protection gear stops them from falling or completely eliminates the chances of injury when they do fall, there is a good chance that those workers also use the gear incorrectly.

Locander advises workers to first read the manual that accompanies their fall-protection gear, as it provides detailed instructions on putting on the equipment and using it with other equipment, such as aerial and scissor lifts. The owner's manual also highlights inspection and troubleshooting procedures.

The fall-protection specialist

Every company that employs people who work on elevated platforms and equipment needs to have a competent person, Locander says. This employee should have taken an eight-hour or longer course on the basics of fall-protection equipment and act as the go-to person on anything related to fall-arrest gear purchased by the contractor. The fall-protection specialist also should be able to identify and remove worksite hazards and train other workers on how to correctly put on equipment.

Every contractor should make sure that a fall-protection specialist is on site if workers are doing elevated work, Locander says. "If the equipment is not being used correctly, it's almost worse than useless. The number of people who are injured or killed in fall accidents is still very high, and in virtually every single case it's by misuse of equipment."

"If you're going to fall, you're going to sustain injuries," says Kenneth Lemke, engineering manager with RTC Fall Protection. "We try to minimize those injuries and prevent serious injury or death."

"If you're on a bridge, for instance, you're going to fall into the harness," Lemke says. "It's like getting into a car accident when strapped to a seatbelt."

Securing yourself to lift equipment

Elevated construction work often involves lift equipment, such as aerial work platforms, boom lifts and scissor lifts. Lift equipment poses an added challenge and safety risks compared to working on building beams or ladders. For one, they can move in almost any imaginable direction.

"Unlike with other applications, with personnel-lifting equipment, you're dealing with something that does not have a fixed anchorage," Locander says, adding that lift equipment equipped with an overhead anchor point — the safest type — is rare. "With fixed anchorage, there are specific requirements as to how much weight the anchorage can bear."

With mobile equipment, you not only have issues of working with no overhead means of anchoring, "but you're also dealing with something that could fall over on its own or fall on top of you if you fall," Lemke says.

RTC makes a product customized for aerial lifts called the Combo Kit, which combines a harness with a lanyard. In typical, non-mobile applications, the lanyard can be detached from the harness, but the Combo Kit's lanyard is sewn on to the back of the harness so that the worker cannot take it off.

"One of the risks with aerial lifts is that the worker will take off the lanyard because of limited mobility," Locander says. "That's possible in other applications because you have another anchor: You can move anchor point to anchor point. But you can't do that if you're working in a lift."

In a lift, the anchor point must have a rated capacity of 5,000 pounds or be designed to support twice the weight of the operator, according to OSHA. The length of the lanyard must be limited to 6 feet in order to reduce the impact force in the event of a fall.

If a manufacturer did not build an anchor point into its lift-equipment, fleets should have an engineer fabricate a 5,000-pound-capacity, steel anchor point that attaches to the lift-equipment's boom, Lemke says. OSHA forbids workers from tying to the guardrail.

If an anchor is unavailable, workers can use a fall-restraint system, which prevents you from going over the edge of the lift.

"If you can fall over, you wear equipment that will stop you from getting there in the first place," Locander says.

The restraint device is very similar to a lanyard used to arrest a fall, but it does not have any shock-absorption qualities for deceleration. A fall-restraint lanyard loops around a guardrail and has two locking snap hooks on each end that attaches to the D-rings on both sides of your harness, limiting you from getting to the actual edge where you can fall over. It's basically like a leash, Locander says.

The guardrail should be capable of withstanding at least twice the weight of a worker's impact force.

Aerial-lift operators must be aware of the dangers of working high up. Many workers who for years have done their job untethered and without injury see no need in fall protection gear, Locander says. "It's only when someone gets hurt that many contractors start doing something about it."