It has been as gradual as a sunrise, but finally it has dawned on equipment-owning organizations that the position of equipment manager is much more than the care and feeding of machines.

A number of factors have shifted the paradigm, including better-built and more sophisticated equipment coming off the production line of original equipment manufacturers, technology innovations that make troubleshooting easier and quicker, advanced oil analysis from laboratories, and improved management system software. The list goes on, but the primary reason for the rising star of the equipment manager is the dramatic change in responsibility.

Louis V. Marino, vice president of equipment operations for Yonkers Contracting Co., has witnessed these changes firsthand. He is responsible for a fleet of 750 pieces of on- and off-highway equipment with a replacement value of $75 million.

How to Write a Business Plan

In the corporate environment, a long view of equipment assets can help build credibility. One way to do that is with a business plan, says Greg Morris, CEM, fleet service manager for Sarasota County, Fla.

“A well thought-out and written business plan can provide a company and its fleet manager with the structure needed to develop a world-class operation, reduce costs and increase productivity,” he says.

Business plans are relevant from a user’s perspective and can be used to move fleet management forward. They provide a strategic direction for the coming year and provide a road map that tells you where you’ve been and where you are going, both short and long range.

“And they validate the need to allocate resources appropriately for organizational needs,” Morris says. “They provide a description of the services you provide, as well.”

Writing a business plan requires much thought and input from the entire equipment team. This enables everyone to understand the direction of the fleet, thus going a long way toward obtaining leadership and management approval, customers’ and fleet buy-in, and establishing transparency and trust.

Morris outlined these components that make up a good business plan:

- Description of services or purpose, such as what you provide, personnel, facility locations, history and services (24-hour service and fuel sites, for example).

- Mission. For example, provide all fleet services from acquisitions, fuel, operations, administration, maintenance and repair to disposal in an efficient, safe customer-service-focused manner.

- Values. Service through technology and training.

- SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats).

- Goals and objectives.

- Financial plan.

- Results expected from the business plan.

- Vision, both short- and long-range.

“The first reason for the increased corporate-level respect for the position is money,” Marino says. “The equipment manager has the responsibility for an extraordinary amount of capital, money that has to do with the overall business.”

In most cases, especially with larger fleets, the corporation has “a lot of money tied up in a lot of iron,” Marino says. “Fleet management is one of the most critical parts of a construction organization.” If equipment isn’t maintained and kept up-to-date, he says, the problems that are created can cut deeply into a company’s efficiency, productivity and profitability.

“The ability to manage the assets of the entire fleet is critical to the whole organization and critical in making the company successful,” he says.

In addition to the increased financial involvement, asset managers have seen new demands develop over the past two decades. Once, the position required a basic knowledge of how to operate and repair a machine. Today, the job description emphasizes the necessity of not only knowing equipment, but, in Marino’s words, “having knowledge of compliance and risk management involved with equipment, especially in areas such as emissions and safety.”

Today’s equipment manager has to interact effectively with field operations, which requires an understanding of how operations work and the ability to interface with operations, he says.

No longer is the equipment manager a mechanic who works for the company, as it was when Marino started his career 23 years ago. Today’s fleet professional is “someone who has a mechanical background, has a knowledge of managing people and assets, and has the financial abilities to understand the financial managers he deals with,” Marino says.

Another factor, he says, is the evolving quality of equipment and the rapid-fire burst of technology that is allowing them to last longer and perform better.

Marino’s personal climb up the corporate ladder typifies one example of how much asset management has changed. He was hired as materials manager for Yonkers after spending eight years working for a smaller construction company.

His initial responsibility at Yonkers was “to get control of an out-of-control situation involving steel, form work and other company-owned materials that Yonkers had on job sites.” He accepted the position with a promise that he would later assume more responsibilities. Working on the materials side of the house brought him into contact with limited equipment, mostly concrete and paving machines. Later he took over the light equipment department. That exposure, however, along with the various jobs he had learned by working at the previous smaller company, provided him with a solid basis for future career growth, he says.

The longer he worked at Yonkers, the more he began to think about how he would run the equipment department if given the opportunity. He knew what changes he would make and how he would do certain things differently. That opportunity came in 1998 when he was promoted to vice president of equipment operations, and “I came in like gangbusters,” he says.

People he had worked with over the years didn’t know how to take him in the beginning, he says. “They could not believe the amount of changes I made in the first six months. They thought I was nutty.”

For instance, at the time of his promotion the company was using a computer system that had been in place for a long time. The information it produced was five weeks old by the time he received it. “It was confusing, and you never knew where all the equipment was in a timely fashion,” he says.

One night, while shopping for classroom supplies with his wife, who is a schoolteacher, he saw a wall full of “blue charts, like calendar charts for each month of the year. I thought, ‘I can use that,’” and he left the store with 30 charts that he carried back to his office.

Marino had white cards made up for each piece of equipment the company owned and had working in the field. Then he mounted the entire array of blue charts outside the main office and put them to use—in addition to the antiquated computer system.

“Every time we moved a piece of equipment, we took the white card from the blue folder where the equipment was working and placed it into a blue folder that represented the new job site,” he says.

When the charts went up, “people thought I was crazy,” he says. In fact, word about the blue charts spread around the company and “even the owner came up to see what I was doing.” When he saw what was going on, he thought it was a good idea. So did the department employees, Marino says.

The blue-chart method was used until about two years ago when a more sophisticated computer system was installed. “I liked the charts,” Marino says. “They served their purpose.”

Another vice president of equipment, Lew Love, also knows how important equipment managers have become to organizations, such as his own company, James Construction Group in Baton Rouge, La. James Construction is a regional contractor that has most of its business in Florida, but also serves Louisiana, Arkansas and Mississippi. About 70 percent of the work is heavy highway construction and 30 to 40 percent is industrial, such as chemical.

“It is essential that equipment managers be integrated into the organization,” Love says. “One reason is that many companies have a large portion of their net worth tied up in assets. That is a huge responsibility. Equipment managers have to make sure those assets are maintained properly and disposed of at the proper time. More important, the manager must properly purchase the equipment at the beginning of its life cycle.”

The second reason the asset manager is essential to the company is the key role he plays in garnering new work. “All companies are about going out and earning new business,” Love says. “Equipment can be a huge part of that. Companies are beginning to realize and appreciate innovative and new ways of approaching rate structures and cost allocations, and being aggressive in capturing new work.”

The new breed of equipment managers brings quite a bit to the corporate table. By astute management of the fleet, they maximize the value of the construction company, says Love. They minimize cost at the project level, no matter how that cost is measured: hours, cubic yards, time, whatever yardstick is chosen, he says.

“Minimizing project cost allows the company to go out and be as aggressive as it possibly can in securing new business,” Love says.

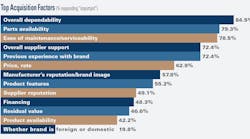

Earning corporate appreciation and respect starts with “buying right” when it comes to the machines purchased, Love says. And that must be done for each application. “You have to make sure you buy the right product that returns the best value to the company,” he says. “And that involves the local dealer and the manufacturer to keep pricing competitive.”

There are no uniform rules that apply when determining what equipment is best. “Every situation is different,” he says. “Your geographic footprint can dictate equipment selection, such as the quality of the dealers in your region. You have to make sure you have quality support in areas where you move equipment around. If not, you have to make sure that your own organization is ready from the ground up to pick up the slack.”

In Love’s case, for example, rocky terrain really isn’t a factor at most of his job sites, “so bucket capacity is more of a consideration than the heavy-duty nature of the stick and bucket as it would be if we were working in a lot of rock,” he says.

The majority of dozers in his fleet, for instance, are low ground pressure (LGP) machines. “We work in poor under-foot conditions, so a low ground pressure machine is a better fit,” he says.

Love’s fleet management abilities were called into play when Hurricane Katrina zeroed in on Louisiana. “We knew that the third-party dump truck companies that we depended on to haul our materials for us would be chasing hurricane-related work, mostly in New Orleans,” Love says. “We all met in the conference room the day after Katrina hit and decided to go out and buy our own dump trucks. We were able to do that in a short period of time with the support of our local dealers.”

Within two weeks, James Construction Group owned a fleet of 20 dump trucks, thanks to Love’s industry knowledge. “This is a relations-based business,” he says. “Having good relationships with people you count on places you in a position of getting things done when you need to get them done. Of course, you have to continue checking to make sure you get quality work, and good pricing on parts and service. But at the end of the day, it is the relationship you develop with suppliers and vendors. And that is the critical part of the process.”

Based on his 25 years in the business, there is no question that the corporate view of equipment professionals has changed, Love says. “An equipment manager used to be perceived as a necessary evil, a person who made sure the oil was changed. Now he occupies a critical box on the organizational chart. Upper management, including CEOs and CFOs, realize the value of equipment managers and want to make sure they have the right person in that position. They have a lot of money tied up in that equipment.”

Climbing toward the summit of an organization isn’t an easy job, Marino says. “You have to have knowledge. And people are an extraordinary fountain of knowledge. You have to educate yourself about every aspect of the industry you work in. You learn and you grow and hopefully good things happen.

“Oh,” he adds. “Hard work helps.”