Iron Works: Under the Big Top

On August 25, 1939, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers awarded Guy F. Atkinson Co. of South San Francisco, Calif., the contract to build Mud Mountain Dam, a flood-control dam on the White River southeast of Enumclaw, Wash. At 425 feet above bedrock and 3 million cubic yards, it was the world’s highest embankment dam until completion of Idaho’s Anderson Ranch Dam in 1950.

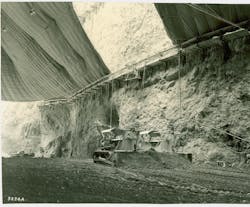

The lower part of the dam was in a vertical-walled gorge 300 feet deep, and Atkinson was faced with significant problems just accessing the site, let alone placing fill at a rate sufficient to meet the project’s schedule.

Access to the canyon floor was initially gained by roads built down to 175 feet above the riverbed to an inclined tramway at the downstream diversion tunnel portal and a stiffleg derrick at the upstream portal, and by cableways over the fill area. Workers hiked in and out on trails, stairways and ladders.

The project’s difficulties were compounded by the area’s four feet of rain and 175 precipitation days a year; the ground typically would not dry at all during the six-month rainy season, yet the fill material had to be kept dry. Moreover, the abundant rain made truck usage in excavation areas nearly impractical, and spoil from the spillway and tunnels had to be hauled by train.

After unsuitable clays were found in the borrow area, the dam was redesigned in 1940 to rockfill, with an impervious rolled earth core. The redesign changed how the fill could be placed; unlike the original earthfill, the rock could be placed in wet weather, and the core material could be dried prior to placement. With the redesign, the contract was renegotiated to a cost-plus arrangement for affected contract items.

A fleet of 20-yard Sterling dump trucks was used to haul rock from a quarry four miles away. The trucks reached the fill by means of a 6,700-foot-long system of concrete trestles built onto the canyon walls, and the rockfill was sluiced into place. Earth fill for the core was hauled by train to a screening and kiln plant on the canyon wall, and after drying was lowered into silos above the core by two more stiffleg derricks. Conveyors forwarded the material from the silos to skips suspended from the cableways, which placed it on the core.

To keep the core material dry during the 1941 season, Atkinson deployed what was at the time the world’s largest tent. Measuring 196 x 380 feet, it was suspended from some 30 miles of cables, and covered the fill and the delivery conveyors. The cableway skips were handled through hatches in the tent, and Cat D8s with LeTourneau dozers pushed the material to its place and spread it. Large voids under overhangs were filled with concrete.

The tent was raised twice during 1941, and was removed that fall. As the fill reached the top of the vertical-walled gorge, the system of derricks and skips was phased out in favor of more conventional means of placing fill. The tent ended up being used by the Corps; in the winter of 1941, it was reconfigured to 30 x 600 feet and mounted on wheels to protect freshly poured 30-foot-wide concrete runway slabs on an airfield at Yakutat Bay, Alaska.

The Historical Construction Equipment Association (HCEA) is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving the history of the construction, dredging and surface mining equipment industries. With more than 4,000 members in 25 countries, activities include operation of National Construction Equipment Museum and archives in Bowling Green, Ohio; publication of a quarterly magazine, Equipment Echoes, from which this text is adapted; and hosting an annual working exhibition of restored construction equipment. Individual memberships are $30 within the United States and Canada, and $40US elsewhere. We seek to develop relationships in the equipment manufacturing industry, and we offer a college scholarship for engineering students. Information is available at www.hcea.net, 419.352.5616, or [email protected].