L-2 Traction Tires

Directional tread maximizes traction and flotation. Big spaces between lugs keeps mud from packing in the tread.L-3 Rock Tire

With twice as much lug as traction tires, it resists cutting better, rides smoother on hard surfaces, and still provides good traction.L-4 Deep-Tread Rock Tire

Same ratio of lug-to-void as the rock tire but the tread is 50 percent thicker to resist cuts and wear longer.L-5 Extra-Deep Rock Tire

Resists cutting and puncture in extreme conditions with 150 percent more rubber in the tread.In This Story:

Off-road tire performance is all about managing weight, distance and speed. There's always a tradeoff—you can carry more weight but not as far or as fast; you can carry loads farther if you go slowly; you can go faster if you reduce the load and/or the distance. Rubber compounds can resist heat buildup and improve haul speeds somewhat without sacrificing as much load or distance. But it took a major design departure—radial-tire construction—to improve load-carrying capacity significantly without the accompanying speed and distance penalties.

Radials' advantage over bias-ply tires stems largely from the fact that they lay tread down on the ground more like a crawler tractor lays down track pads. When tread on a radial casing makes contact with the ground it makes a firm, rectangular footprint. Because a bias-ply casing is made up of multiple body plies, it is less flexible than the radial's steel-belt package, so the tread tends to distort as it comes under load. The lugs of rubber also tend to squirm or scrub in the tire's footprint. Rolling resistance is greater, and a bias tire generates more heat than a radial. If the tire gets too hot, it can come apart under load.

To get the firm footprint (and the accompanying traction, cooler operation, and improved fuel economy) off-road equipment manufacturers are moving toward radials. Equipment designers like cooler-running radials because they can carry heavier loads longer and faster.

According to the Rubber Manufacturers Association market numbers, five years ago just over half of the off-road construction equipment in North America rolled from the assembly line on radials, and less than 40 percent of replacement-tire purchases were radials. Today, 70 percent of new, wheeled construction equipment is shipped with radials and 64 percent of the replacement market is radial.

When manufacturers started designing equipment with specifications exceeding radial performance (go-anywhere articulated dump trucks and titan haulers such as Caterpillar's 350-ton 797), radial-tire design had to adapt. To improve traction and stability for ADTs, tires became wider. The wider tires put more rubber on the ground for better grip, and more air volume in the casing to increase load-carrying capacity.

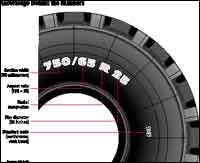

Tire guys describe broad groups of tires in terms of aspect ratio, which is the ratio of sidewall height to cross-section width. Conventional haulage tires, where the industry started, are considered 100 Series, with the sidewall height nearly equal to the cross-section width. (Most actually have an aspect ratio of about 96.)

Wide-base tires are the 80 or 85 Series (most with actual aspect ratios of 83). The section-width designation molded into the tire sidewall and used to identify these products is typically a whole number expressed in inches followed by a fraction. One very popular size is the 20.5 R25.

The section width of a similar-sized conventional (or 100 Series) tire is designated by a whole number. The conventional tire that a 20.5 R25 might replace would be a 16.00 R25. Most wide-base (or 80 Series) tires are designed to have the same outside diameter as their conventional counterparts, so they can be retrofit without affecting the vehicle's gearing or ground speed.

As ADTs gained popularity and users demanded better traction and flotation, tire makers developed 65-Series tires, with sidewall heights that are only 65 percent of the tread width. These tires are typically called low profile, and their short sidewall became attractive to wheel-loader designers who wanted additional traction to crowd the pile. That traction reduces wheel spin, filling buckets faster and reducing tire costs. The low sidewall and wider footprint of a 65-Series tire adds stability that helps silence operator objections to radials.

With less sidewall to flex, low-profile radials ride more like bias-ply tires than conventional radials.

"There's still a perception problem out there with operators who have never used radials before because radial tires feel different. And the larger the loader you get, the more you're going to feel that difference," says Chris Rogers, general manager of marketing at Bridgestone/Firestone Off-Road Tire Co. "It takes a while for an operator to get used to that feel, but once he does, the machine will be much more efficient. "Low-profile tires reduce that initial uneasiness."

In the three most popular tire sizes, about 7 percent of OEM installations are low profile and 2 to 3 percent of tire replacements are going with low-profile tires. BFOR numbers suggest that for the one most popular tire size (the 20.5 R25), about 10 percent of OEM applications are low profile and 3 to 4 percent of replacement tires are low profile.

But 100 percent of the giant 63-inch tires used on Cat's 797 haul truck are wide-base, 80-Series radials, and virtually all ADTs come with low-profile 65-Series radials. The vast majority of large wheel loaders roll off the assembly line on low-profile tires, too.

"We're seeing rapid change in the market as OEMs put low-aspect-ratio tires on more new machines," says Michael Ford, market segment manager with Michelin. "Haulage tires used to be all 100 Series, and now they're moving to 80 Series. Loader tires used to be 80 aspect ratio, and now many of them are down to 65 aspect ratio. The main reasons have directly to do with productivity—better traction and better flotation. They're also getting less cutting and chipping in the tread face because of reduced ground-contact pressure."

Low-profile tires seem to exaggerate the benefits of radial tires, including the trend toward lower inflation pressures. Because they generate less heat, radials carry the same load at lower inflation pressure than bias tires. Low-profile radials carry the same load as radials at even lower inflation pressures because they're designed with greater air volume to support the load. Lower inflation pressure reduces the risk of puncture because the tire is able to envelop a sharp object, rather than applying stiff resistance that can be cut.

"If you can go with the lower pressure within a recommended inflation-pressure range for an application—meaning you can run within the ton/mile-per-hour recommendation at a lower air pressure—you're going to improve cut resistance," says Rogers. "But every construction application is so different, you really do have to do your analysis site by site before settling on the best pressure for the job."

Most scraper tires are wide-base 80 Series, primarily because they improve flotation. The scraper competes better with ADTs. Cut resistance is often a significant motivation as well. Even some motor graders have moved from wide base to 65 Series low-profile tires in order to harness their horsepower.

The logistics of tire delivery also encourage some low-aspect-ratio tire use. Before 63-inch tires were designed for Cat's 797, the biggest tires on the market were 57-inch monsters that could range up to 13 feet in diameter. In order to take the tires for a single truck to where the vehicle is being assembled, you need special hauling permits.

To manage the load capacity of the world's largest mechanical-drive haul truck, the designers needed more air volume. But a taller tire would be nearly impossible to transport on the highway. Not only was a low-profile tire's increased flotation likely to absorb more shock and cutting loads, it was also more reasonable to deliver.

Goodyear's introduction this summer of a two-piece tire assembly has the potential not only of improving the logistics of delivering very large tires, but also changing the way wear is managed. The assembly consists of an independent casing that engages a tread belt along two ribs molded into its inner diameter. Slide the tread belt onto the casing, line up the rib with the grooves molded into the casing's outside diameter and inflate. You get a 57-inch mining-truck tire.

"The footprint is 11 percent greater than a traditional 57-inch off-the-road tire," says Perry Marteny, team leader for Goodyear's off-the-road tire programs, "which provides more-uniform pressure distribution and leads to much improved traction."

The assembly acts like a conventional tire, with coefficients of friction between the two pieces measured at levels that promise very tire-like performance. The assembly has some interesting potential to reduce tire costs, especially if you have an application that tends to wear out the tread before the casing. The worn component can be replaced without having to dispose of the other part of the tire. And Goodyear's people say they've changed tread rings with as little downtime as 20 minutes.

Because the casing and the belt can be separated for shipping, and are both a little more flexible as components than a tire is, it's easier to ship them over the road.

"The current model is a 45 R57—a 57-inch tire like the 40.00 R57. But you can't get six 40.00 R57s on one flatbed," says Marteny. "You can easily put enough two-piece assemblies to shoe a truck on a single flatbed trailer."

The Goodyear assembly, designated TPA (two-piece assembly), is available only in conventional aspect ratios at the present time. It's possible that the technology could be adapted to create a larger, wide-based assembly that could be delivered more easily than the 63-inch tires to sites where the mammoth trucks work.

"Goodyear doesn't currently produce a 63-inch tire (like those for the biggest haul trucks)," says Marteny, "but the two-piece assembly could allow us to penetrate that part of the market."

As you may have noticed, radials in their various aspect ratios, and now two-piece tire assemblies, have multiplied the number of alternatives to the conventional bias-ply tire.

"More and more, tires are being optimized for different applications," Ford says. "Twenty or 30 years ago, it was pretty easy to buy construction tires because there weren't so many choices. Now there are more manufacturers, with application-specific tread designs, sizes and rubber compounds."

To further complicate the decision, there are some tire applications—low-speed jobs with very high incidence of cutting damage—where bias-ply tires are still a wise selection.

Using rubber similar to what the manufacturer put on the machine is probably a safe choice for utility machines, but the broad array of options promise greater productivity and efficiency for high-production units. Matching aspect ratios, tread designs, and specific rubber compounds can tailor tire performance to the application. To get the right ride for your machine, you just need to know some basics and find a tire vendor you can trust.