Work platforms mounted on telehandlers offer an option for giving workers access to elevated tasks, but using the platform safely and productively is largely a matter of remembering the many things this equipment combination cannot do. Because they're not designed with the same safety equipment as an aerial work platform, telescopic handlers should only lift people to heights under limited conditions.

"Before you use a man basket on a telehandler, you have to remember that the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) B56.6 standard says to use it only if no other means of doing the work are feasible," says Gary Riley, president of Aerial Work Platform & Telehandler Training & Consulting in St. Louis, Mo. "If you have a job that a rough-terrain boom lift can do, then you need to get the boom in there."

Perhaps the heart of the problem is that people are tempted to use a telehandler to lift people any time it helps them finish a job no matter what equipment is at hand.

"I've seen a roofer raise a pallet of shingles with a telehandler, shut the machine off, and climb up the boom to work from the pallet," says Charlie Bowman, Star Equipment Rentals in Des Moines, Iowa.

Attempting to prevent people falling from forks or pallets, the industry created work platforms with approved guard rails and tie-off points and load charts for use with telehandlers. These platforms must be accompanied in the field by literature that proves their compliance with ANSI safety standards, and the telehandler manufacturer must approve the use of each specific work platform with its machines. (Not all manufacturers approve their telehandlers for lifting personnel, by the way. Those that do not will apply warning decals to their machines. Those warnings must be heeded regardless of whether or not the work platform in question meets safety standards.)

Inevitably, though, a work platform/telehandler combination is not the same as a rough-terrain personnel lift, and users must know and accept their limitations in order to work with them safely. The most obvious difference between the two forms of powered access, of course, is that the person in the platform doesn't have control of the machine.

The operations and safety manual for JLG's Telehandler Personnel Work Platform clearly states that an "Operator must remain in the cab and keep platform occupants in direct line of sight" any time the platform is in the air.

"Now that you're working at heights, you (the worker in the basket) must be in charge of your own destiny — you've got to be able to come down when you want to come down," says Riley. "Somebody has to be present at all times at the telehandler's controls because there are people in the basket. Safety standards don't directly say that (but it is implied)."

Before anybody goes up in the platform, the occupants and telehandler operator must establish a means of communication. Most use two-way radio, but as crane operators who use radios will tell you, being able to talk to each other doesn't necessarily mean communication will be clear. Combining voice with hand signals can help clarify any ambiguity.

"I don't care what hand signals you use, just make sure the guy in the basket and the guy at the controls are using the same signals," says Bowman.

There are safety professionals in the industry who simply aren't willing to risk botched communication, considering the risks.

"AWPT (Aerial Work Platform Training) only supports use of telehandlers and work platforms with integrated controls on the platform," says Tony Grote, executive vice president of AWPT. AWPT is the North American subsidiary of the International Powered Access Federation, a non-profit organization that promotes safe use of access equipment. "That way the operators themselves, in the platform, have control and they're operating in a similar fashion as an aerial lift."

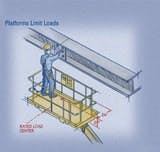

One of the reasons a maker must approve each model of work platform used with its telehandlers is that each combination requires a unique load chart. Allowable loads will be significantly less with a work platform than with forks because forklift capacity is typically rated using a 48-inch homogeneous cube. The load center is on the machine center line, 24 inches in front of the carriage and 24 inches up from the forks. The load center in an occupied work platform is always moving, and virtually always above and/or beyond the 24-inch load center of a homogeneous cube.

Jeff Stachowiak, national safety director for Sunbelt Rentals, uses a simple example to point out how much the position of the load center can alter a telehandler's capacity.

"You are operating a reach forklift with a 6,000-pound load rating according to the load chart in the cab. The load you are picking up is right in front of the forklift and you will not have to extend the boom to pick and place the load. The load weighs 5,000 pounds, but the load center is at 36 inches from the back of the forks." Stachowiak asks: "Can this lift make the lift?

"The correct answer is no. You can calculate the actual load on the forklift this way. A 6,000-pound rating times 24-inch load center equals 144,000 inch-pounds. Then 144,000 inch-pounds divided by 36-inch load center equals a 4,000-pound load limit. So this 6,000-pound forklift can only pick up 4,000 pounds if the load center is at 36 inches," Stachowiak explains. "This calculation works for all forklifts."

"Rental customers will come in and ask for the biggest machine they can get, and think they can do more than they can with it," says Star Rentals' Bowman. "A 55-foot telehandler at maximum forward extension won't lift 1,000 pounds. A 16-foot platform with a big guy and some tools in it will weigh more than 1,500 pounds."

That's heavier than many telehandler operators expect a work platform to be. Problems arise most frequently with some bad operating habits.

"Most operators will start a lift by angling the boom up, and then boom out," Bowman explains. "That's good. But when they get ready to come down, some operators will boom straight down without retracting if they can.

"The key to safety is to know how to read the load chart," Bowman adds, "and most guys don't read the arc. The telehandler's capacity is going to be smaller when you get to the bottom of the arc."

As the boom angle diminishes, if the boom is not also retracted, the load descends in an arc, moving away from the center of the telehandler as it comes down. Vertical columns on the load chart indicate the load limits at various combinations of boom angle and boom extension. Simply booming down, the load will pass from one column on the load chart to the next farther away, always moving to lighter load limits. If the load in a work platform is near the telehandler's limit at height, it will overload the machine before it can be boomed to the ground. The telehandler will tip forward.

Finding out how much load is to be lifted is an operator's first priority. Certified platforms are labeled with their weight. If labels are lacking, transport drivers who haul the platform to the site can often tell you how much the platform weighs to within a hundred pounds or so.

Find out how much the tools and materials to be carried in the platform weigh, and then add a reasonable factor for the weight of each equipped worker on the platform — typically 250 to 300 pounds. Then operate safely within the load-chart limits for the combination of that particular work platform and telehandler, not the telehandler with forks alone. Two workers with tool belts represent 600 pounds or more. Even working within the forklift's rated capacity (established at 24-inch centers), if both workers move to one side of the platform to do something, the machine could topple.

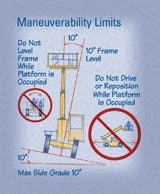

Because of its oscillating rear axle, telehandlers work from a triangular base defined by lines drawn from the ground-contact patch of the front tires to the center point of the rear axle and the front axle. This not only means a telehandler is less stable than a machine with a rectangular footprint, but it also indicates that the machine becomes less stable as raising the boom pulls the machine and load's center of gravity to the rear.

If the boom is raised but not extended, the center of gravity moves to the rear, into the sharp point of the stability triangle. That's why it is important to level the machine frame — either by repositioning the machine, deploying outriggers, or by using frame sway — before raising the boom.

"A telehandler doesn't have the safety features that a man lift has," says Bowman, referring to the tilt indicators that will lock out an aerial work platform's boom functions rather than allow an operator to raise the basket from an inclined base. Telehandlers rely on the operator to make the right call.

Don't use a telehandler's frame-leveling feature after the boom is raised. The dynamic lateral force can throw the center of gravity outside the reach forklift's triangular footprint. Manufacturers also prohibit leveling the telehandler frame with people in the platform.

Dynamic forces are magnified through the telehandler's structure to the work platform —even when the boom is in transport position. They're unpredictable enough that OSHA regulations prohibit driving a forklift when there are people in a fork-mounted platform. The Code of Federal Regulations, at 29CFR Subtitle B, 1926.451 says "Forklifts shall not be used to support scaffold platforms unless the entire platform is attached to the fork and the fork-lift is not moved horizontally while the platform is occupied."

So the telehandler/work platform combination is restricted to maneuvering only when workers are out on the ground. When people are in the platform, the machine should be limited to boom functions.

Many telehandlers have a ride-control feature much like that used in loaders. It makes moving materials around a site much more productive, but is not a confidence builder for platform workers.

"There's a lot of bounce built into that boom," says Bowman. "Even if you're just repositioning for a better angle on a lift, you need to bring the boom down, get the operator out on the ground, reposition the machine, and then try the lift again."

Like boom-lift operators, occupants of the telehandler platform have to wear a full-body harness with a lanyard attached to an authorized lanyard anchorage point in the platform. Attach only one lanyard per anchorage point. This gear isn't fall protection, it is intended to keep workers from being catapulted out of the platform in the event of a sudden boom movement. A 4-foot or shorter lanyard is recommended to keep the person inside the guardrails.

People should not move from the platform to structures or vice versa when the boom is in the air unless it is absolutely necessary. When a transfer is necessary, it should happen through the platform gate, with the platform within 1 foot of a secure structure. OSHA requires 100-percent tie-off using two lanyards. One lanyard must be attached to the platform with the second lanyard attached to the structure. The lanyard connected to the platform should not be disconnected until the transfer to the structure is safe and complete.

Anyone on the platform must wear approved head gear (hardhats). Check clearances overhead, on the sides and bottom of platform when lifting or lowering. Always look in direction of movement.

"The telehandler driver has to have a certification card indicating that he is OSHA certified," says Bowman. "And the certifications are brand specific. You have to be certified for the brand machine you're using."

Pins that secure the platform to the forks should always be put in place before raising the platform. Those pins should be attached by cables or chain to the platform.

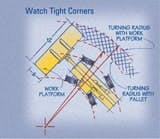

Operators working with large platforms should be aware that anything wider than eight feet will broaden the telehandler's effective swing radius through turns.

"A 16-foot platform extends the telehandler's turn radius to the left and the right because it is wider than the tires," says Bowman.

The carriage-tip function in the cab is off-limits when people are in the platform.

"The ANSI B56.6 standard says the only time you can use a forklift to lift personnel is when there is no other alternative. But there always is an alternative," says Stachowiak from Sunbelt, which does not rent telehandler platforms. "That's why they make boom lifts and scissor lifts."

Clear communication between the telehandler operator and the worker in the platform is not only essential to safe and productive telehandler/work platform work, it is required by OSHA. Many operations use two-way radios, and combining voice with hand signals clarifies and creates a back-up option to keep a job rolling.

| In this story: |

|---|